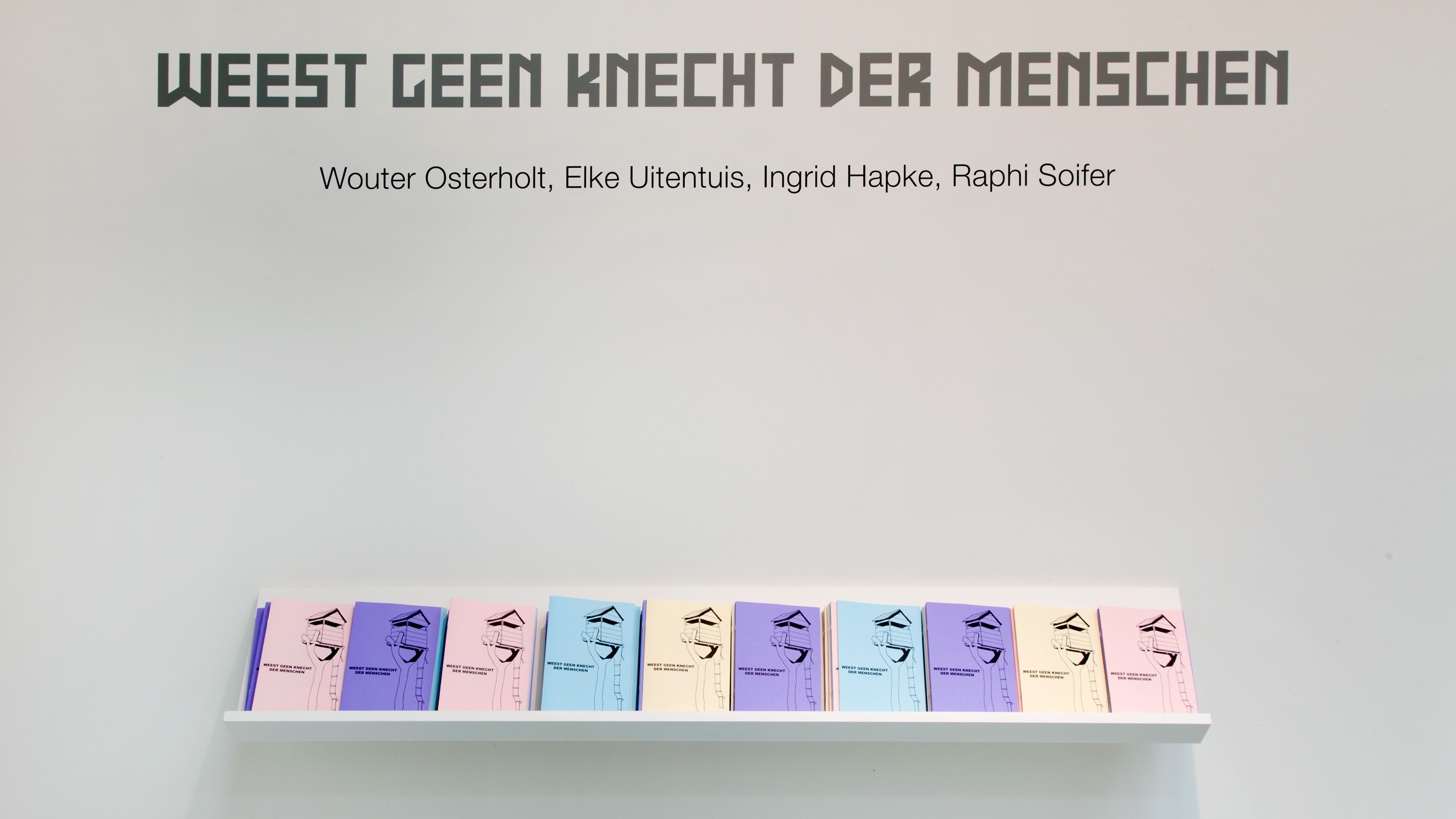

(Old Dutch for Be not a Servant of Men*) is made in the context of the exhibition, ‘Horizons – art in a changing Friesland’ at the Frisian Museum in Leeuwarden, an institute that collects and exhibits objects and artworks with an emphasis on the Frisian identity and culture. The project situated itself beyond the limited scope of the local horizon and positioned the idea of the Frisian cultural identity in a more global perspective. It looked at the relation between the Mennonites, a religious movement with Frisian roots and the Ayoreo, an indigenous tribe from Paraguay. The project exists of five elements: a site-specific intervention, textile work, two channel video work, photograph and a publication.

The Mennonites are Protestant Christians who base their ideas on the teachings of Menno Simons (1496–1561), an Anabaptist religious leader from Witmarsum, a village in Friesland. Throughout centuries, the Mennonites kept their religion despite persecution by the various Roman Catholic and Protestant states. Rather than to fight, the majority survived by fleeing to neighboring states where ruling families were tolerant of their religion. Pacifism became a key characteristic for the Mennonite movement. The geographical spreading of Mennonites followed a trajectory from Germany to Russia and later to North and South America.

The Mennonites arrived in Paraguay at the beginning of the 20th century and are mostly situated in the Gran Chaco, a sparsely populated lowland with thorn forests divided among eastern Bolivia, Paraguay, northern Argentina and Brazil. Different semi-nomadic indigenous tribes have always populated the Chaco. Until mid-19th century the tribes lived an undisturbed and isolated live. In recent times the natural landscape of the Gran Chaco is rapidly transformed due to the arrival of large-scale agro-industrial and cattle ranching companies.

The Mennonites played an important role in this cultivation process of the wilderness. They were the pioneers who overcame the difficult conditions, creating areas with a flourishing agriculture. The Mennonites ‘cleared’ the road for large agricultural industries that are destroying the remaining wilderness. Because of the rapid change of the landscape, the indigenous people were forced to adapt to a new lifestyle. This project examines this transformation and looks closely at the conflict between the Mennonites and the Ayoreo community.

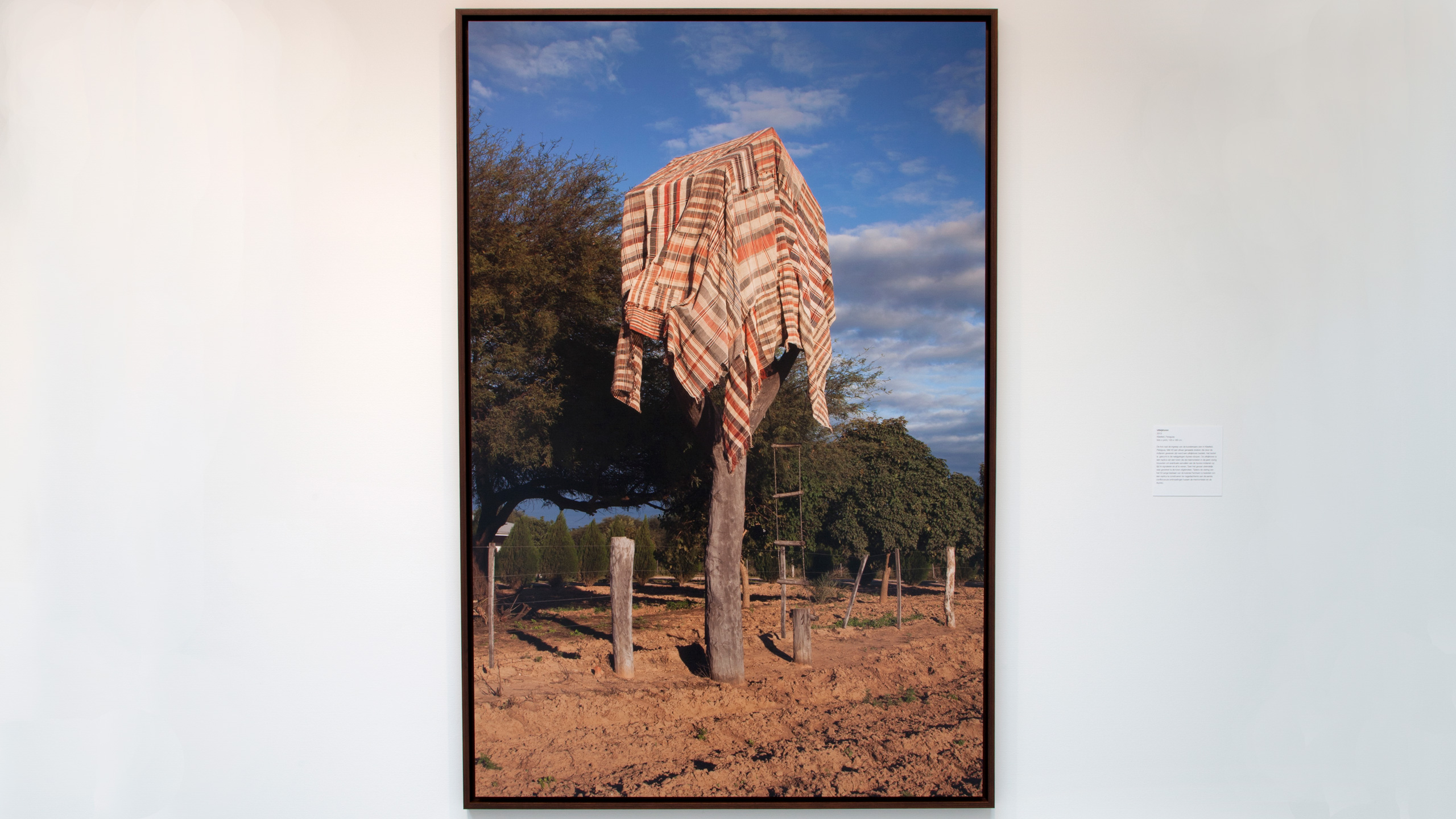

The work started with a temporary intervention in Kleefeld, a small village in the north-west of Paraguay. The patchwork cloth was made of 50 different Ayoreo textiles, bought in neighboring Ayoreo villages and from local tourist shops. The cloth was used to cover up a Mennonite watchtower, which was constructed as part of a defensive strategy in order to protect the Mennonites community from attacks from the Ayoreo. The watchtower was used in the 1960s and commemorates the first conflicts between the Mennonites and the Ayoreo. This intervention was photographed and showed in the exhibition.

In the exhibition the patchwork fabric was used for a replica of a banner that we found in the museum of Filadelfia in Paraguay. It reads “Gemeinnuß vor Eigennuß”, old German for “public benefit before self-interest”, an important moral law within the Nazi Party (NSDAP). The banner originally decorated the facade of the community house of the Fernheim colony in 1935. As part of the National Socialist propaganda, the slogan was used to strengthen social cohesion among Germans at the expense of the groups that were systematically excluded. Mennonites in the 1930s were influenced by what was happening in Germany and so the motto was also used as a moral building block in the development of the Mennonite Colonies. In the pioneer days, great importance was placed on mutual cooperation. This created strong cooperatives that played an important role in the colonization process of Chaco territory. The work in the exhibition juxtaposed the two oppositional sides, the Mennonites versus the Ayoreo. The former represented by the black letters forming the words “Gemeinnuß vor Eigennuß”, made from leather from cows that occupy Ayoreo land. And the latter by the patchwork of textiles, forming the underlying landscape of occupied Ayoreo territory. The work portrays the current political landscape and is meant as a provocation in order to start a dialogue on the colonial history and how that led to the contemporary social segregation.

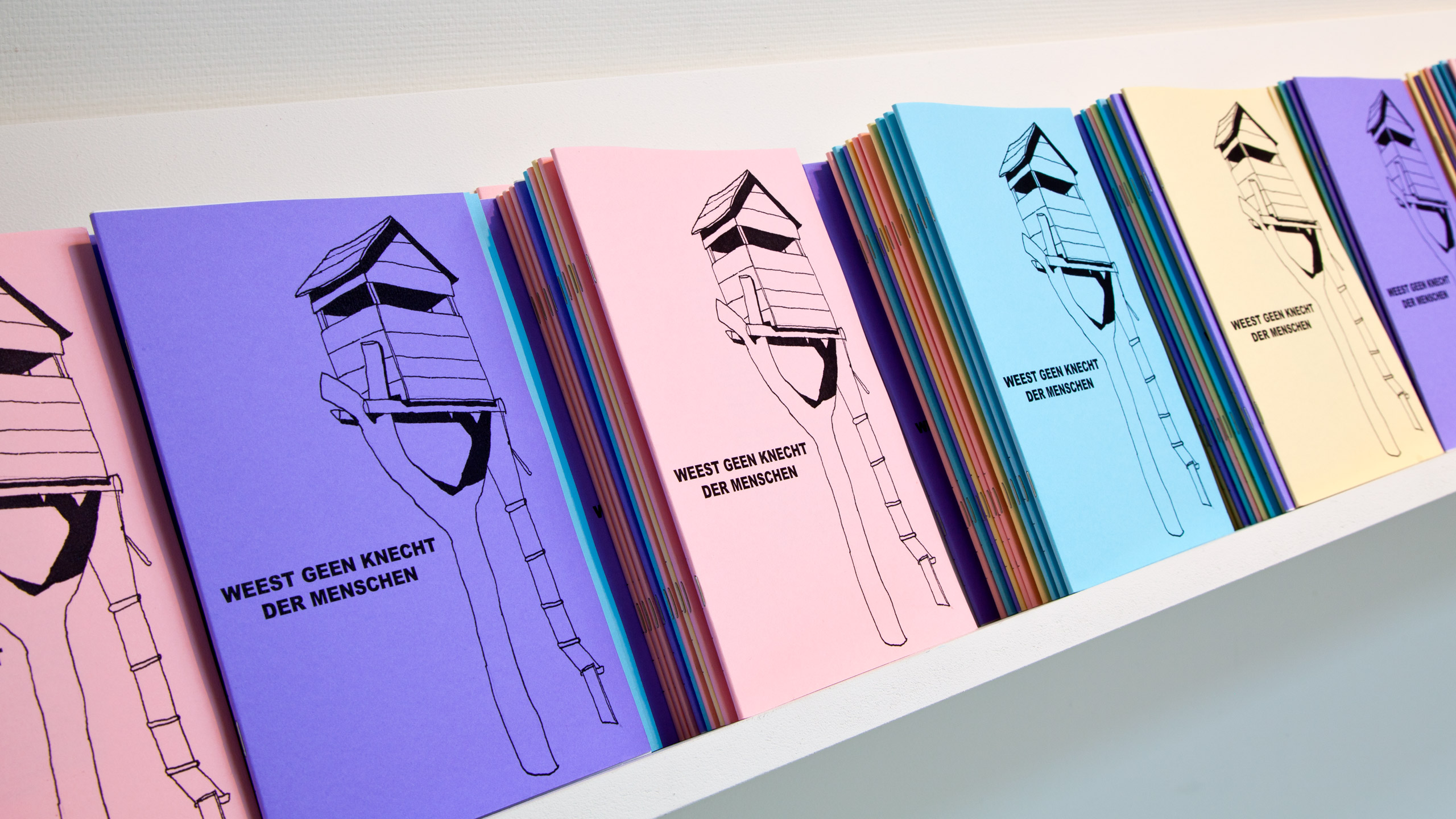

The two videos show interviews with both Mennonites and Ayoreo in which they reflect on the encounters between the two groups. Questions were asked about the past but also about current social issues and about their future vision of further developments in the Chaco. The design of the publication is based on Mennonite schoolbooks that are used in missionary schools. It contains four essays written by Gabriella Dyck, Ingrid Hapke, Raphi Soifer and Elke Uitentuis/Wouter Osterholt. The texts critically analyze the complicating factors within the project and the political situation in the Mennonite colonies in general.

* The title of the work are the last words of Menno Simons on his deathbed, “Weest geen Knecht der Menschen, ghelijc als ic geweest hebbe” (old Dutch for: “Be not a Servant of men, like I have been”). Simons regretted that he had agreed to banishment from the community as punishment for a sin. He thought that was too severe a punishment and actually always believed in the power of dialogue. However, peer pressure had forced him to agree. He had felt uncomfortable with the strict rule for the rest of his life. In retrospect, he would have liked to have turned against general opinion for the sake of ideological consistency. After all, Simons was a strong advocate of preserving individual autonomy within the group. However, the prospect of eventual exile kept him in check.